Made in Westminster:

The source of the USS ‘crisis’ – and the solution

In our letter to the Guardian we wrote that

[The USS ‘crisis’] is the result of the misrepresentation of the finances of the USS, and the desire of a new breed of university managements to cut their pension liabilities and thereby ease the financing of new buildings and campuses.

Successive Pension Acts have encouraged managers of private sector schemes to exaggerate the risks of default. Combined with Quantitative Easing, this has led to a headlong abandonment of Final Salary Defined Benefit to “Defined Contribution” schemes, where employees rather than employers bear investment risk.

Higher Education today is shaped by frantic competition for students and huge building projects. Universities can recruit unlimited UK undergraduates paying an annual £9,000 plus, backed by taxpayer loans. The Higher Education and Research Act 2017 even allows universities to go bankrupt.

Much of this argument will be familiar to colleagues. The debate about the University Superannuation Scheme (USS) deficit has been an active subject of discussion on campuses since last summer when the press first announced that the pension scheme was at risk. Initial press claims were of a deficit of £17.5bn, while at exactly the same time USS themselves reassured pensioners that the scheme was in surplus.

But it is worth considering the source of this deficit in more detail than the Guardian letter’s pages will permit.

Is the deficit real, as the employers and USS themselves have asserted, or is it an accounting artefact, as the UCU trade union has claimed?

This is a key question, of course. Most important of all, until we know the source of the deficit we cannot begin to propose solutions.

In the letter we attributed the reported deficit to three causes.

- Pension Acts and associated government regulation of private sector pension schemes

- Quantitative Easing and government monetary policy

- The impact of the Higher Education and Research Act 2017 on the financial behaviour of universities

We will turn to these shortly. First we need to summarise briefly the methodology that is used for valuing USS.

How USS is valued

The USS is obliged by the Pension Regulator, an arm of Government (technically, a ‘non-departmental public body’), to triennially review the valuation of its assets and future liabilities. Future liabilities are estimated on the basis of a number of actuarial assumptions, including life expectancy for men and women, projections of wage and consumer price inflation, and so on. Several of these assumptions have been criticised for over-estimating the liabilities. Small changes in assumptions can have very large consequences thanks to the effect of compound interest.

In the most recent valuation, it has been the method for valuing the assets of the scheme that has been the focus of most public challenges.

At the time of writing in February 2018, USS has its investments in some 70% stocks and shares, which are high yield but high risk, and around 10% in government stock and gilts: low yield and low risk. The remaining 20% or so is in a number of other investment vehicles. Over the last five years the investments have performed well, and the last Annual Report was able to boast that the assets had grown by an average of 12% per annum for the last five years to £60bn.

One might think that the scheme should be valued in terms of the assets it holds. Suppose you own a house and you want to use your house value to ease your retirement. Your principal concern will be about the market value of that house in the future (and future remortgaging conditions).

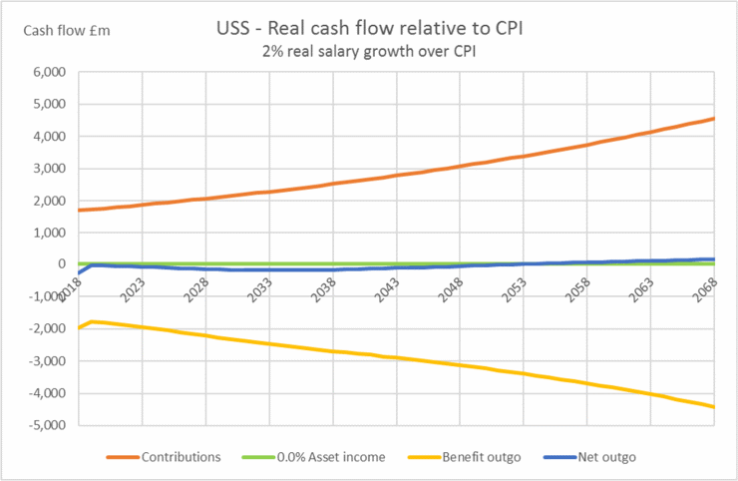

Working for UCU, First Actuarial examined USS’s actual assets, its income projections (contributions from the sector) and pension liabilities. They found that income and liabilities closely match for the next 40 years without touching the assets.

That is, if no action were taken, USS would be able to pay its pensioners well into the future without even touching its assets. Its assets could therefore continue to be invested in a mixed portfolio, and (although past performance is no guarantee) grow at a rate exceeding inflation. Like the house buyer, they are not about to sell their house at current market prices.

However, this is not how USS values its assets.

Instead, the USS valuation uses a method called “self-sufficiency in gilts”. In the 2014 USS valuation this was sometimes referred to as a “Gilts+” methodology. A new test, “Test 1”, was introduced which placed further conditions on this valuation. But essentially the idea is as follows.

- Assume that USS closes tomorrow. In order to guarantee payments to pensioners it needs to shield assets from stock market variability.

- To do this, it moves its assets from the current mixed portfolio dominated by stocks and shares to government stocks and gilts (for reasons of brevity we will refer to a range of government stock investments as ‘gilts’, although technically the term applies more narrowly).

This process is called “de-risking” because government stock is meant to be secure — far more stable than an individual stock price at least. It means selling stock at current prices and buying gilts, and predicting future gilt yields.

Unfortunately gilt yields are very low, and likely to remain low, thanks to Quantitative Easing (see below) undermining the UK Government’s credit rating and sterling value. Crucially, they are likely to stay well below inflation for the near and long term.

Note that this is a counterfactual assumption. Assets are still 70% invested in stocks and shares. It is not a model of the running of the scheme. It is a model of what would need to happen if the employers ceased to operate. If all universities went bankrupt tomorrow, staff would not be paid, and USS would receive no employer and employee contributions. The scheme would close, and would then have to pay out its liabilities.

The obvious question has to be whether sectoral bankruptcy is a meaningful basis for valuing this pension scheme. (Note: some in the pensions industry are questioning whether it is a reasonable basis for valuing any pension scheme.)

Private sector pension scheme regulations say that valuations must take place by modelling this scenario. In the case of single-employer schemes, the worst-case assumption is important. Employers like BHS and Carillion were the sole employer paying into their pension schemes. The single employer can declare bankruptcy, leaving the pension scheme to pay out entirely on its assets. But the 68 large pre-92 Higher Education institutions who are the principal members of USS are not a single employer. (USS cites 350 employer members, but most are small.)

The model assumes all institutions go bankrupt simultaneously.

This is an extraordinary assumption, one that in political terms can be said to have zero probability. That is, if the entire pre-92 university sector declared bankruptcy, I would contend that the government of the day would be faced with a political crisis of unprecedented scale, compelling them to intervene to protect staff, students and pensions.

Moreover, if the government of today is genuinely envisaging this scenario, they have a political obligation to say so, and explain now what they will do about it!

There has been no instance of a single bankruptcy of a pre-92 university since USS was established. Instead, universities have been obliged to merge, teach out courses and thereby transfer staff and students. Thus when University College Cardiff was in financial difficulty in 1987, it merged with the University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology (UWIST, also in some difficulty) and the University of Wales College of Cardiff, to become Cardiff University.

This means that even in cases of financial hardship for one institution the sector itself may continue to grow. The joint and several liability for the pension scheme means other employers pick up the tab, just as they grow market share.

Let us consider the shocking scenario where a large Russell Group university declares bankruptcy. This is a more realistic possibility than sectoral closure. It is a scenario newly envisaged by the Higher Education and Research Act. Instead of being obliged to manage ‘institutional exit’, as the 2016 HE White Paper euphemistically called the process, the legislation now permits, in theory at least, an institution being permitted to shut down overnight. Worse, let us also assume that the Government takes a zero-intervention approach, and does not fund a gradual withdrawal from the undergraduate market.

The exit of a large player from a market of many competing institutions may be a severe shock, causing (say) 10,000 USS active members to be without employment, and their contributions to cease. In 2017, USS had a total of 190,546 active members (those paying into their scheme). In the short term, USS would lose 5% of its income.

Note: the figure of 10,000 reflects one of the big institutions like UCL. There are 68 pre-92 university employers out of the 350 participating employers. Considering only these employers would obtain an average of 2,802 active USS members per institution.

But markets with many players can absorb market share relatively easily. Students will need to move somewhere, and staff will be required to teach them. Grant-funded research activity is hypothecated (funding is earmarked solely for that purpose) and much of it will relocate, with staff. So the redundancies will be absorbed by employment elsewhere. In other words, the obligation to share risk across the sector is, in fact, offset by the ability of institutions to absorb market share.

None of the above is intended to be blasé about the human and social consequences of a large bankruptcy of this nature. Rather, it is to point out that for USS, these consequences should not be exaggerated.

Yet exaggerating the risk of bankruptcy lies at the heart of this valuation model.

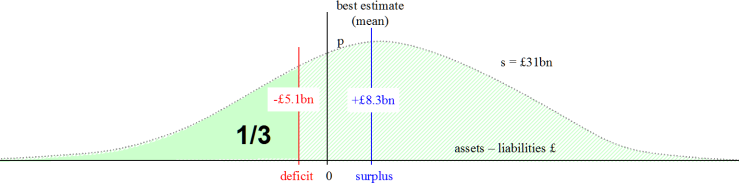

The result of the USS valuation in September 2017 was the following distribution. Using a model of gradual de-risking over the next ten years, the mean projected deficit (‘the best estimate’) was £8.3 billion in surplus. The sketch below illustrates the principle. The distribution is approximately Normal, and symmetric.

The deficit is the lower bound of a 33% confidence interval of £8.3bn ± 13.4bn. (The standard deviation is an astounding £31bn). There is thus a one in three chance that the actual deficit will be more than £5.1bn. But there is a two in three chance that the deficit will be smaller than £5.1bn, or the scheme will be in surplus.

Indeed, the zero point is 0.27 standard deviations below the mean, a probability of 0.21 of the area on the left hand side of the mean. There is a 60% chance that the assets will outstrip the liabilities, and a below 40% chance that (in the imaginary situation of gradual scheme shutdown), the assets will not meet the liabilities.

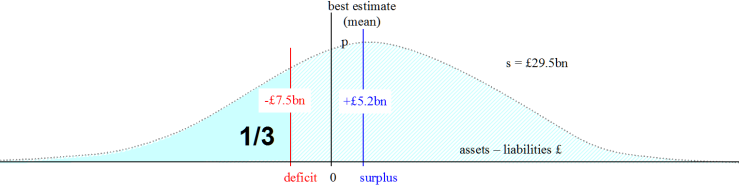

Of course, this entire model hinges on the need to de-risk. What happens if the scheme de-risks immediately? The university employers’ federation Universities UK asked this question in November last year. Having consulted their members, they concluded that the sector would not like to carry the theoretical declining risk of a mixed portfolio for the next ten years, and would wish to model immediate de-risking. This obtained the following graph.

Again, the scheme is in surplus. But thanks to the fire-sale of assets and the greater exposure to the below-inflation value of gilts, the projected mean declines to £5.2bn. The lower bound of the 33% interval (0.43 standard deviations) is -7.5bn. The projection has become slightly more certain. Applying the same calculation as before, the chance of scheme default has increased from 39.5% to 43%.

Indeed, conducting ‘de-risking’ under current market conditions is a sure-fire way to turn a projected deficit into an actual one. The actuarial term is extremely misleading. Actual de-risking is not only counterfactual, it would be an imprudent way to manage the pension scheme!

Now that we have understood the valuation method currently in operation, we can consider the three causes outlined in our letter.

Cause 1: The Pensions Acts and the Pension Regulator

There have been a flurry of Pensions Acts since 2004. There were Pensions Acts in 2004, 2007, 2008 (which established automatic enrolment), 2011, 2014 and 2017. The key ones for our argument concern the office of the Pension Regulator.

The Pension Regulator was established by the Pensions Act 2004. On paper, a Pensions Regulator is a good thing, attempting to ensure through intervention that private pension schemes are self-standing in the circumstances where an employer goes bankrupt.

However, the regulatory requirements of the Pension Regulator primarily concern Defined Benefit schemes. These schemes have an “employer covenant”, a legal obligation for the employer to guarantee defined benefits should the employer go bankrupt. As bankrupts cannot pay bills, this duty means intervening in the valuation and regulation of live schemes. The Pension Regulator insists on cautionary estimates of pension scheme deficits.

The 2014 Act introduced a new statutory duty on the Pension Regulator. This is

to minimise any adverse impact on the sustainable growth of sponsoring employers when exercising its functions relating to scheme funding.

The Pension Regulator has a number of statutory obligations, the central one being of course to ensure that pension schemes do not fall into deficit. But the new statutory duty of 2014 places the commercial interests of sponsoring employers over the responsibility to fund private sector pension schemes. As Willis Towers Watson comment

It will be important to think through arguments [for corporates] to defend against any methodologies which result in building in excessive prudence through the back door.

The obvious point is that modelling a multi-employer pension scheme (especially one whose income stream is an hypothecated section of public sector finances) as if it were a single employer is absurd. Modelling any risk of default on a zero-probability event is to model a zero probability. The real chance of deficit is zero, unless USS themselves pull the plug and ‘de-risk’ the scheme. Indeed the way to risk deficit is to do precisely this.

Therefore the Pension Regulator simply needs to accept that the valuation method being used is meaningless, and recognise that efforts to address a non-existent deficit risk are counter-productive. They are examples of ‘excessive prudence’.

Cause 2: Quantitative Easing

Quantitative Easing is the process whereby since the 2008 banking crisis, first Labour and then the Conservatives have increased money supply (‘printed money’) to bail out the banking sector. The current manifestation of QE is the retention by the Bank of England of artificially low interest rates. This has had the effect of pushing up the cost of buying gilts but depressing their rate of return (yield).

Gilt yields increased after the vote to leave the EU, but to a peak of 1.1%. But this has been overtaken by inflation.

The crucial factor for a pension fund is whether gilt yields exceed CPI. If all the assets are in gilts, any below-inflation growth is a real-terms decline in asset values. Inflation erodes the pension assets. This is precisely why early de-risking (despite its name) increases the chance of scheme default.

Cause 3: The Higher Education and Research Act and its precursors

Government HE policy since 2010 culminated in the Higher Education and Research Act 2017. This commenced with the introduction of £9,000 a year undergraduate fees and the partial abolition of the block grant (total abolition for Arts and Humanities). Universities found that they could make a tidy profit by ‘pile em high’ practices. But they were still restricted in the numbers of students they could recruit.

This all changed with the removal in 2014 of caps on student numbers. Universities could now compete with each other for students, and market share. The first set of victims have been the post-92 universities, the ex-polytechnics, whose staff are not in the USS pension scheme. Students considering an expensive degree at London Metropolitan University, for example, now found places at King’s College. In London, LMU’s pain has been swiftly followed by that of Westminster University, currently engaged in serial cutbacks of staff.

In this first wave, the USS employers have boomed. Indeed, the Higher Education Statistics Agency reports that sector surpluses rose by a factor of 10 from £158m in 2005/6 to £1.5bn in 2016/17. However, to accommodate the new student numbers, universities needed estate capacity. They started a major programme of investment in new buildings, campuses and student accommodation. To do this they needed to borrow. Whereas some initial loans may have been on favourable terms, as construction costs have increased, institutions have had to borrow on the open market.

Of course, when you borrow in this way you have to declare your assets and your liabilities, including the liability toward the pension fund. It is this new obligation that I believe explains why, in the USS negotiations, UUK employers (led by the most expansionist Russell Group employers) focused on Defined Contribution, rather than, say, a worse Defined Benefit scheme.

This is because a shift to Defined Contribution removes any future liability the employers have towards the stability of the scheme. It ends the employer covenant.

Conclusion

The fight over the USS pension is the first national dispute over the finances and shape of the UK Higher Education sector since the enactment of the Higher Education and Research Bill as an Act. Market competition and the new regulatory environment are causing employers to try to limit their liabilities and reduce their costs. One can read the specific solutions proposed by the employers as signifiers of their priorities towards staff more generally.

When we wrote the Alternative White Paper for Higher Education, we did not predict that the first victim of the new HE regime would be university pensions. But the links between government policy, institutional behaviour and the USS ‘crisis’ are not hard to see.

- For decades USS was strong and stable. There is no evidence that any intrinsic factor has changed. USS has a set of internal regulations and parameters for managing stock market risk. There is no need to ‘de-risk’ the portfolio.

- The deficit is a projection under imagined conditions. It is counterfactual, and not real.

- To compound this observation, even in these impossible conditions the scheme is odds-on to achieve a surplus. The deficit that arises is an artefact of the scale of uncertainty assumed in the model.

What has changed in the reporting of the scheme finances has been due to the pressure of the Pension Regulator to report finances on the mathematically incoherent ‘self sufficiency in gilts’ basis, and the impact of Quantitative Easing on this gilts-based modelling.

All three of these extrinsic factors arise as a result of Government policy, whether they be Pension Acts, QE or the fees-and-loans market in education.

If we want to fix the ‘crisis’ in the USS pension scheme, the rational solution is to address its causes directly. A compromise solution that leaves the valuation methodology in place invites future cuts in the scheme.

We need to fix the problem at source.

The Government could take any of the following steps:

- instruct the Pension Regulator to move deadlines,

- instruct the Pension Regulator to set aside the self-sufficiency valuation requirement,

- agree to act as guarantor of last resort until the next valuation cycle,

- opt to put money into the scheme / buy a stake in it,

- engage in full nationalisation.

Given that the risk of scheme default is actually zero unless the USS Board order a disinvestment programme (choose to ‘de-risk’), for the Government to agree to act as a guarantor of last resort is an extraordinarily cheap intervention.

Moreover, providing this assurance to scheme Trustees until the next valuation would also permit the National Audit Office to review the valuation methodology and propose rational alternatives. USS is required to value the scheme every 3 years and to do so in a way that considers long and short term, but it is not required to use the current approach.

This is a crisis Made in Westminster — and the solution lies in Ministers’ hands. There is already an Early Day Motion 619 signed (at the time of writing) by 65 MPs. The problem and the solution lies in Westminster.

It is time to resolve this dispute by preserving the scheme as-is.

In the meantime, staff in universities are absolutely correct to strike. Unless they do, Government minds will not be concentrated.

The main problem we faced in campaigning over the HE Bill was not that we did not convince senior Government figures of our analysis. It was that there was not a mass movement outside of Parliament to defend our Universities.

That has all changed with USS.

See also

- There’s no deficit – and here’s my working – Sean Wallis

- Letter to Guardian: University pension ‘crisis’ triggered by HE market madness

- Early Day Motion 619

- Holmwood et al (2016). The Alternative White Paper for Higher Education. London: HE Convention

- Salt and Benstead (2017), Progressing the Valuation of USS, London: First Actuarial

- USS Annual Reports

- London Region UCU demonstration 28 February

Lobby your MP

First, check whether your MP has signed Early Day Motion 619:

Next, write to your MP in your own words. Ask your MP to add their name to EDM 619.

Thanks for that thought-provoking post.

LikeLiked by 2 people

So why are strikes threatened, its not the pensions is it, just the other remuneration and employment conditions surely?

LikeLiked by 1 person

The strikes are in response to the imposed cuts in the USS pension that are premised on this projected deficit. If the deficit were removed, there would be no pension changes and no strikes.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this excellent post

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for this post. Very clear and very helpful. Will share.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A reasonable valuation of the assets taking into account the plural nature of employing institutions is of course a big issue, but the calculation of the liabilities needs also to be taken into account.

Final salary scheme pensions are calculated based on the best year in a period of some 12 years prior to retirement updated by inflation (CPI now rather than the previous RPI). University staff salaries have been held down to well below both measures of inflation for a decade or more. This means in the coming years the salary base used in pensions calculations of many staff with significant years of service will actually begin to fall reducing, not increasng, USS liabilities for those staff.

As many in universities and some vice chancellors (e.g. Imperial and Edinburgh) have now been suggesting it is essential that a fair and transparent valuation of assets on a proper considered basis (not some simplified worst case scenario) and the liabilities (using the real data on salaries) is done by some group able to do a proper evidence and data based analysis, not using some unbelievable formulaic approach. This needs to be thorough, detailed and transparent so it is accepted by all sides before any change is made to the current USS scheme so soon after the recent significant changes. The evidence base will also be needed if challenges to regulator formulae or government rules are necessary.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You make some good points Austin. I should point out that USS is no longer a Final Salary scheme but a Career Average Revaluated Earnings one.

LikeLiked by 2 people

In terms of the liabilities calculation it is a mix of previous and current schemes Sean… but my point, as I am sure you realise, is that a proper calculation is needed ased on real data and not some simplistic and silly formulaic one.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for an excellent article – by far the most informative I’ve read on this subject.

LikeLike

Overall, this is a good analysis, but I don’t agree with some aspects of it and with some of your conclusions. Although pension schemes are required to report “self-sufficiency in gilts”, the actual metric used by USS and most other schemes is “technical provisions” (TPs). TPs are *not* an objective way of determining the deficit. Rather they represent a self-reflection of the Trustees on what they believe to be the discounted value of their liabilities, which is the uncertain element in the deficit calculations. Crucially, the Trustees and their consultants use information provided by the employers, and specifically their attitude to risk, to formulate TPs, which are then certified by the actuary. This therefore is not primarily a regulatory crisis: it is a crisis of confidence of the employers in their own schemes, which in turn has driven the TPs de-risking agenda. I suspect you are right in identifying the ulterior motives behind the risk aversion of many institutions. Although a legislative intervention would help, the first step in solving the crisis is for employers to reverse their stance towards risk, and re-instate their confidence that the DB scheme is viable for the foreseeable future. Even then, getting the genie back into the bottle will be neither cheap nor quick.

LikeLike