Huge loan hikes for students — are staff caught in the crossfire?

Across UK Higher Education we are beginning to see a new wave of course closures and redundancies.

- De Montfort University in Leicester has announced 65 job losses — despite having £120m in the bank. Although in 2021 the university reported a small deficit (£3.7m) due to Covid, this was easily offset by the £15m surplus of the year before.

- Wolverhampton University has ‘paused’ undergraduate recruitment across 146 courses, and is aggressively pushing a voluntary severance scheme. The university’s financial statements from 2021 reveals £125m in reserves. But according to the Guardian, ‘Wolverhampton’s deputy vice-chancellor blamed the cuts on the university’s £20m budget deficit and a 10% decline in undergraduate applications.’

- Roehampton University in London sent out 226 letters to about half their academic staff telling them they were going to be ‘at risk’ of redundancy. Cherished courses would be axed and existing students would be taught to completion by casual staff (or existing staff compelled to accept fixed-term contracts).

These cuts dwarf even the Goldsmiths College cuts to History and English & Creative Writing announced earlier this year. The new group are all ‘post-92’ universities, unlike Goldsmiths.

But Goldsmiths reminds us that initial purges are likely to become a cycle of multi-year cuts. Staff who remain are not safe. Colleagues at Roehampton have suffered job culls in 2018, 2020 and 2021, and were just recovering from the last when they received these letters.

In a tuition fee marketplace, any university making significant closures will inevitably find it harder to recruit students. After all, students want to know that their degree programme, and their university, will be recognised by employers ten, twenty, even thirty years in the future. There is a real risk that universities can become locked into a ‘death spiral’.

Roehampton University was one of a group that in 2020 blinked first. On paper it was running a £4m deficit budget and believed that student numbers would fall at the start of the pandemic. Instead, student numbers rose by 2% overall. But Roehampton, already committed to a cuts programme, was in no position to capitalise on the increase. The university’s financial statements for 2021 reveal no real improvement on its financial position despite the cuts, and only £10m in reserves.

Even when departments are excluded from cuts, the damage to the credibility of the university ‘brand’ can affect student recruitment in other courses. London Metropolitan University was the first victim of tuition fee market changes, shrinking by two-thirds within a few years, even before the announcement of the tripling of the undergraduate student fee from £3,000 to £9,000 in 2010.

What is triggering these cuts? Why are they happening now? And what can be done about it?

Was this to do with the recent 2021 Research Excellence Framework (REF)? Universities have a history of hiring and restructuring to ‘game’ the REF. However, it is clear that redundancy plans were developed well in advance of the REF publication date. Indeed, Wolverhampton boasted of excellent REF results in the areas in which they submitted, and Roehampton University also claimed to have excelled in the REF. So an unexpected loss of so-called ‘Quality Related’ income does not appear to be the cause (QR income has not yet been announced).

All these universities — indeed most universities, even the most research intensive — depend primarily on student tuition fee income. And the main reason why business managers identify courses for closure is because they perceive that they will be loss-making, and cannot see how to turn them into profitability.

As the quote from the Wolverhampton deputy vice chancellor indicates, universities are looking anxiously at UCAS student recruitment figures, and attempting to determine whether students will follow through with applications.

Roehampton’s case is a little different, and goes back further, but underlines the same basic point. Faced with problems in domestic undergraduate recruitment, the university chose to ‘diversify’ towards international recruitment and FE. But although the university is less susceptible to student loans changes, the strategy has clearly not worked.

The latest published UCAS data from January 2022 indicates a slight downward variation from 2021 (610,720 applicants across all four nations compared to the 616,360 at the same point in the recruitment cycle last year). This is not the final deadline for applicants, and in fact the application rate is slightly up as a demographic proportion (43.4% of school-leavers compared to 42.6% in 2021). Indeed the 18-year old application rate continues to increase.

So there appears to be nothing in the published application data that should trigger panic.

But this data was sampled before the Government announced its Augar-inspired plans for the student loan scheme, and as inflation was only just beginning its recent stellar rise.

Donelan turns the screw

The Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS) summarised the Government’s changes introduced by Higher Education Minister Michelle Donelan:

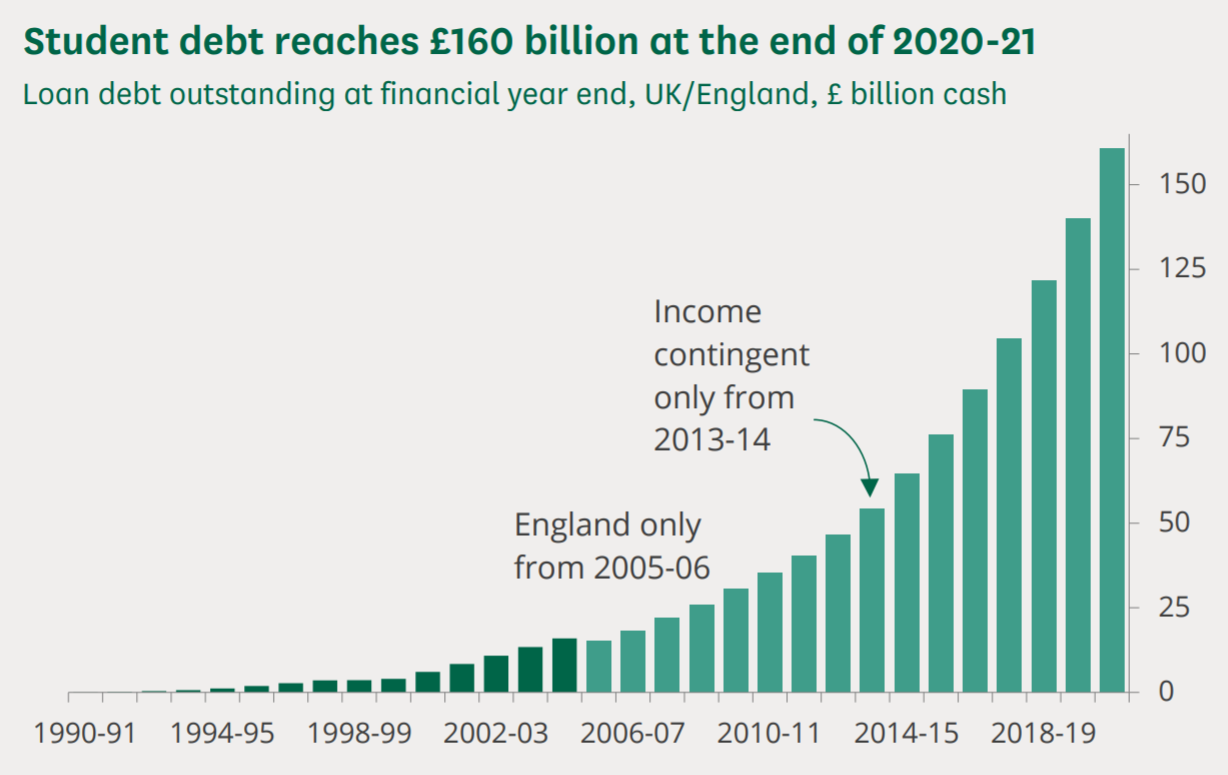

At the end of February, the government announced the most significant reform to the student loans system in England since at least 2012. The central planks of the reform are a lower earnings threshold for student loan repayments (cut to £25,000 and then frozen until 2026–27); a change in the future uprating of the earnings threshold from the rate of average earnings growth to the rate of RPI inflation; an extension of the repayment period from 30 to 40 years; and a cut in the maximum interest rate on student loans to the rate of RPI inflation (from a maximum rate of RPI inflation plus 3%). The new system will apply in full from the 2023 university entry cohort onwards, but the 2012 to 2022 entry cohorts (‘Plan 2 borrowers’) will also see significant changes.

Many may have missed the fact that a single change, concerning the mechanism for uprating the earnings threshold in the future, will also impact on existing undergraduates and the 2022 intake. The IFS calculate that for lower-earning professions, where students are unlikely to pay off their student loan over their lifetime, 2022 students will pay some £20,000 more than they would have expected to pay had these changes not been imposed.

Before Donelan’s changes, the student loan scheme might be best described as a hybrid graduate tax, one where only higher-earning graduates can expect to actually repay a substantial proportion, and the majority were simply taxed at 9% above the threshold for 30 years. The average ‘RAB’ rate was below 50%, meaning that less than half of the loan was expected to be repaid over 30 years.

But following these ‘reforms’, the loans become more like conventional index-linked Treasury-backed loans, with a much lower repayment threshold. A drop in this threshold means that far more students will have to pay something, and those who pay will have to make a bigger contribution. The IFS calculate that 70% of students will be made to pay back RPI-indexed loans in full over their lifetime.

As the IFS point out, these cuts will bite hardest for student cohorts from 2023. But the effects are beginning to be felt now.

Is the market bubble beginning to burst?

From the university management’s elevated positions above the fray, over the last decade the market system has appeared to have been nothing short of miraculous. Despite rising costs for students, student recruitment has tended to keep on rising.

University managements have scrambled to compete for students, but one fact has remained constant — a very large number of UK students have applied for UK university degrees. Despite Brexit and the pandemic, both shocks to the system unforeseen by David Willets in 2010, student numbers have continued to rise.

However, the university fee system is very sensitive to marginal variation. Since most costs are fixed, a 1% increase in student numbers can translate into a 10% rise in profit (officially: ‘surplus’). The last two years have seen a 2% increase each year. But these increases have been distributed unequally between universities, leading to many commentators to demand a reintroduction on student caps and market regulation.

Although the per-student home undergraduate fee cost is controlled and has not risen with inflation, these increases, garnished with taught postgraduate and overseas student fees, have proved lucrative to Vice Chancellors. Undergraduate teaching, the bread-and-butter of universities, continued to pack in the lecture halls, even if during the pandemic many of these lecture halls became virtual Zoom rooms.

It was almost as if the student fee system could defy the laws of the marketplace.

But gravity can only be defied for so long.

Around the edges, some universities started to plan for Augar changes leaked into Government-supporting press. Last year, London South Bank University closed History and Human Geography undergraduate degree courses, and a range of masters programmes. Aston closed History and language courses. Sheffield closed Archaeology, and Leicester purged staff from Critical Business Studies.

It was not all bad news. In Liverpool, the local UCU branch successfully resisted job losses in the Faculty of Health and Life Sciences by an industrial action campaign. And a campaign in Chester saved many jobs.

Vice Chancellors have continued to seek job losses, and course and department closures as a mechanism for refocusing degree programmes for market competition. But the latest round of redundancies are on a greater scale than before.

A toxic combination?

We should be careful not to speculate about UCAS application figures, although some university managers are clearly worried. At the start of the pandemic, like many at the time, we thought that home undergraduate applications would go down. Instead they rose.

But many lower- to middle-income families considering sending their eighteen-year olds to university will be doing the sums. On the one hand, post-pandemic labour shortages mean more better-paid job openings for school-leavers. This opportunity, which did not exist during the pandemic period, may turn out to be short-lived.

On the other hand are the rising costs of university attendance. Even if the loan scheme changes can appear a long way off, they inevitably prey on the mind of parents, if not students. Facing costs going up, more students may choose to study from home, avoiding increasing rents and hall fees. But this assumes that students live near a university they wish to attend. And it reduces one lucrative source of income from universities, that of student accommodation.

Inflation is also hitting the universities through rising fuel costs.

What can we do about this attack?

The first thing we have to say is that the hike in student loan repayments represents both an increased tax on knowledge for the next generation and a socially regressive restriction in access to knowledge.

The Donelan ‘reforms’ are an attack on social mobility. Universities like Wolverhampton and De Montfort, and indeed Roehampton and Goldsmiths, are what John Holmwood of the Campaign for the Public University memorably termed ‘the heavy lifters of social mobility’: regional universities that served a regional working class and middle class population. These are universities that recruit a higher proportion of non-traditional students, Black and disabled students, single parent returners and others, than the so-called ‘redbrick’ or Russell Group universities.

The ‘reforms’ are also a (negative) price signal to working class students aiming to study STEM subjects, including in the more prestigious universities. Whereas law or medicine may be well-paid, many sciences are rather less so, especially in pure research. The mainstay of university pure science research jobs has long been students from working class families.

We should therefore oppose these ‘reforms’ on principle, whether or not they lead to job losses and course closures. They are an attack on students past, present and future.

But looming large for university staff is the threat that these future changes will impact on them very soon. We may already be beginning to see signs that some students in the 2022 cohort are deciding not to go to university in the face of rising costs and financially more promising alternatives. And if 1% increase means a large upswing in projected surpluses, a 1% decrease can be devastating.

We should rally around and support staff whose jobs are on the line — not simply because we should defend university jobs, but because the staff and their unions are in the frontline for the battle for the future of UK Higher Education.

Some practical suggestions

The Donelan cuts can be reversed. What one Government can do, another can undo. As the IFS point out, they position the UK as an international outlier in relation to the proportion of costs borne by individual students.

This is a sector with record surpluses, but a decade of market competition has undermined collective responsibility for Higher Education.

Vice Chancellors see themselves as CEOs of competing ‘HE providers’, not guardians of their sector. Statements of social responsibility are limited to press releases.

Historically, universities that found themselves in a loss-making position like Roehampton would be candidates for merger with other universities, brokered by HEFCE (or other national funding councils). But HEFCE has been replaced by the Office for Students, whose then-chair Sir Michael Barber infamously said that ‘no university is too big to fail.’ The logic of market acquisitions in the post-2016 marketplace is limited to TUPE-transferring a few prestigious teams, and cherry-picking staff they might wish to recruit.

These changes are being imposed at the same time as the UCU trade union is engaged in serious industrial disputes across the UK including marking boycotts in some universities. These disputes are about the basic terms and conditions of university staff, and the USS pension scheme, which has also been undermined by market pressures.

- UCU branches can be contacted for support and solidarity:

- Colleagues should talk to their local UCU or EIS trade union branch and Student Union about organising meetings and protests about the Donelan changes.

- We should support protests called by the National Union of Students and local student unions. Representatives of the Council for the Defence of the British Universities (CDBU) and Campaign for the Public University (CPU) can be invited to speak.

- The Donelan ‘reforms’ are an assault on the aspirations, the hopes and dreams of the next generation. They impose an austerity of the intellect.

We can join the demonstration called by the Trades Union Congress (TUC) on June 18.

As the TUC say, it is time to Demand Better from this government!

We should make common cause with all of those protesting against the Government’s austerity programme. Our demand is not to prioritise the university system above every other societal need. But if we don’t speak up for Higher Education, who will?